|

| Home | What's New? | Cephalopod Species | Cephalopod Articles | Lessons | Bookstore | Resources | About TCP | FAQs |

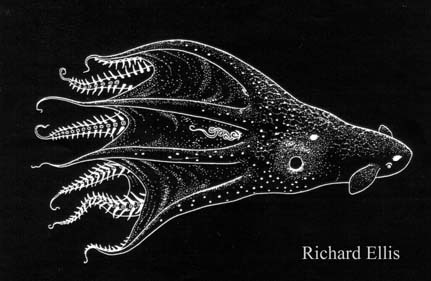

Introducing Vampyroteuthis infernalis, the vampire squid from Hell<< Cephalopod SpeciesAs an example of the mysterious nature of the deep-water cephalopods, consider Vampyroteuthis infernalis, whose name can be translated as "vampire squid from Hell." About a foot long, this deepwater denizen is among the most fascinating animals on earth. It was first described in 1903 by Carl Chun, a German teuthologist who identified it as an octopus, because it had—he thought—eight arms. Then another pair of thin arms was discovered, tucked into pockets outside the web that connects the eight arms. Taxonomically speaking, it hovers between octopus and squid in its own order, the Vampyromorpha. (Note from JW, the order is now "Vampyromorphida" following Sweeneny and Roper 1998).  The type specimen was taken on the Valdivia expedition in the Atlantic Ocean, and was illustrated by the expedition's artist, a fellow named Rübsamen. Subsequent specimens have been collected from tropical and subtropical waters all over the world, usually from depths of 3,000 feet or more, in the abyss where no light penetrates. The first specimens seemed to have two pairs of paddle-like fins, but when one with a single pair appeared, it was believed to be a separate species. Rübsamen's drawing, now in the Zoological Museum of the University of Berlin, showed only two fins, so the original description was of a two-finned animal. Further study (mostly by Pickford) revealed that in the original drawing, one of the pairs of fins was erased, so it has now been concluded that only a single species exists. The very young forms have two fins, the intermediate stages have four, and when the animal reaches maturity, it reverts to its two-finned form. The type specimen was taken on the Valdivia expedition in the Atlantic Ocean, and was illustrated by the expedition's artist, a fellow named Rübsamen. Subsequent specimens have been collected from tropical and subtropical waters all over the world, usually from depths of 3,000 feet or more, in the abyss where no light penetrates. The first specimens seemed to have two pairs of paddle-like fins, but when one with a single pair appeared, it was believed to be a separate species. Rübsamen's drawing, now in the Zoological Museum of the University of Berlin, showed only two fins, so the original description was of a two-finned animal. Further study (mostly by Pickford) revealed that in the original drawing, one of the pairs of fins was erased, so it has now been concluded that only a single species exists. The very young forms have two fins, the intermediate stages have four, and when the animal reaches maturity, it reverts to its two-finned form.

For its size, Vampyroteuthis has proportionally the largest eyes of any animal in the world. A six-inch specimen will have globular eyes an inch across, approximately the size of the eye of a full-grown dog. At the end of its body away from the tips of its arms, Vampyroteuthis has two retractable fins that have reflective surfaces, but the rest of its body is a velvety brown. (Between Panama and the Galapagos in 1925, William Beebe's Arcturus expedition hauled in "a very small but very terrible octopus, black as night, with ivory white jaws and blood-red eyes." Beebe refers to this creature as "Cirroteuthis spp.," but it appears to have been Vampyroteuthis.) Vampyroteuthis may compensate for the blackness of the abyss in which it lives by being equipped with an astonishing series of photophores; lights all over its body—except for the inner surface of its web—that it appears to be able to turn on and off at will. In the back of the "neck" are clusters of more complex photophores, and behind the base of the paired fins, there are two more light organs, equipped with a sort of "eyelid" that the animal can close to shut off the light. "The lack of an ink sac," wrote Pickford, "is also in accordance with the bathypelagic habits of the species, although it strongly suggests that the animal must have other means of masking its own phosphorescence." Until very recently, it was thought that the vampire squid was a weak swimmer, and its weak-muscled, gelatinous body suggested drifting rather than darting as its primary method of locomotion. It has a highly developed statocyst, the organ that controls its balance, which indicated that it descends slowly, further enhancing the idea that Vampyroteuthis was an almost passive predator. Imagine the surprise of researcher Bruce Robison, watching the transmissions of a robot camera deployed in Monterey Canyon off the coast of California, when a specimen of Vampyroteuthis darted into view. Discussing their observations in an article in the New York Times (Broad, 1994) Robison, Michael Vecchione, and James Stein Hunt were absolutely amazed. "The images completely blew my mind," said Vecchione. "Nobody suspected it acted like that—buzzing around in circles and swimming rapidly. Usually they've been pictured as drifting with their arms spread out." The article continued: "Research from submersibles, manned or unmanned, continues to reveal heretofore hidden and often totally unexpected aspects of the lives of these creatures. Everything that was written about this animal was that it was a slow, sluggish sort of cephalopod," said Hunt. "But when you actually see it alive, doing flips and carts and trailing that thing and moving all over, it's clear that it has to be re-written. We have to re-think the animal."(*) _______________________________________________________ (*) One of those who has had to "re-think the animal" is me. In my Monsters of the Sea (Knopf, 1994), I wrote, "Based on the careful analysis of its morphology, and knowing the depths at which it can be found, we can only speculate on the life style of the vampire squid. It appears to be a weak swimmer, and may not even swim at all. Instead, its gelatinous body is weak-muscled, which suggests drifting rather than darting, and its web may serve as a "parachute" to enable it to float downward in search of prey." _______________________________________________________ In a 1995 Scientific American article, Robison described Vampyroteuthis as "the size and shape of a soft football," and then recounted another observation calculated to redefine our perceptions of this most unusual cephalopod: "My colleagues and I have discovered that this strange animal has a bioluminescent organ at the tip of each of its arms. Vampyroteuthis somehow uses these light sources by swinging its webbed arms upwards and over the mantle, which turns suckers and cirri outward and changes the animal's likeness from a football into a spiky pineapple with a glowing top. This maneuver covers the animal's eyes, but the webbing between the tentacles is apparently thin enough for it to see through. We have observed this transformation frequently but remain at a loss to explain exactly what function this unusual behavior might serve." Color pictures of Vampyroteuthis at MBARI References and CreditsCreditsText and illustration lifted with permission from "Deep Atlantic" by Richard Ellis.ReferencesSee "Deep Altantic" by Richard Ellis.Sweeney, M.J. and C.F. Roper. 1998. Classification, type localities, and type respositories of recent cephalopoda. In Systematics and Biogeography of cephalopods. Smithsonian contributions to zoology, number 586, vol 2. Eds: Voss N.A., Vecchione M., Toll R.B. and Sweeney M.J. pp 561-595.

| ||||||

| Home | What's New? | Cephalopod Species | Cephalopod Articles | Lessons | Resources | About TCP | FAQs | Site Map | |

|

The Cephalopod Page (TCP), © Copyright 1995-2026, was created and is maintained by Dr. James B. Wood, Associate Director of the Waikiki Aquarium which is part of the University of Hawaii. Please see the FAQs page for cephalopod questions, Marine Invertebrates of Bermuda for information on other invertebrates, and MarineBio.org and the Census of Marine Life for general information on marine biology. |